Why it’s a good thing for the church that people are leaving white Evangelicalism

Is white mainline Christianity growing? Maybe not.

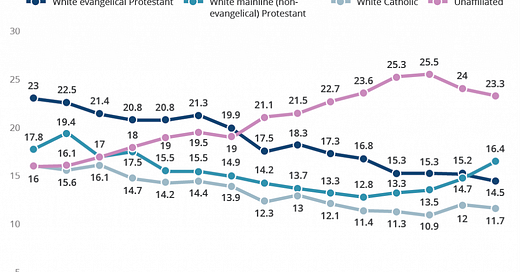

Last week the Public Religion Research Institute released a significant poll that showcased a decline in White Evangelicalism and an increase in white mainliners. It was shocking, because for the first time in the studies that PRRI has done, we saw more people no longer identifying as white Evangelicals. Equally important is the decline in “white nones,” or people who identify as “unaffiliated.”

Does this mean that white mainline Christianity is growing? It’s hard to say because of PRRI’s methodology. Here’s how PRRI framed the question to participants:

“All respondents who identify as Christian are then asked: ‘Would you describe yourself as a “born again” or “evangelical Christian,” or not?’ Respondents who self-identify as white, non-Hispanic, Protestant and identify as born-again or evangelical are categorized as white evangelical Protestants. Respondents who self-identify as white, non-Hispanic, Protestant and do not identify as born-again or evangelical are categorized as white mainline Protestants.”

The methodology isn’t bad for deciding who is no longer an Evangelical. Terms like “born again” are essential to the Evangelical world view, but it is not great for telling us who is in a mainline church. So my mainline friends may want to refrain from celebrating because their churches are growing. I’m not sure that’s what the survey is suggesting. However, there is reason to celebrate.

An exodus from white Evangelicalism since Donald Trump’s presidency

As you see above, white evangelicalism has been on a decrease since 2014, where it enjoyed a brief bump, but white mainliners have been increasing since 2016. The timing here is important, too. Donald Trump’s election wasn’t an aberration, but a systemic result of committed actions of Evangelicals, to make Evangelicalism a reactionary, fear-based, patriarchal, violent sect of Christianity that promoted White Nationalist values. Kristen Kobea De Muz makes a very compelling case for this transformation in her excellent book Jesus and John Wayne.

White Evangelicalism is becoming synonymous with White Christian Nationalism. The Jan. 6 insurrection was a Christian insurrection. That’s a sad story for white Evangelicals that have been trying to resist Trump’s influence, but I think it is too little, too late. White Evangelicalism is dying is because many white Evangelicals only realized it was in trouble after Donald Trump. But the writing has been on the wall for decades. And many Never Trumpers wrote it on the wall themselves. It was a self-inflicted wound.

It is good for Christianity if it rids itself of toxic influences. It is good for Christianity if White Nationalists are ostracized. It is good for Christianity if white Evangelicalism is on a decline. The movement has become so toxified by nefarious influences that the good that’s left in it is not worth saving. Put another way, it's impossible to reclaim white Evangelicalism without being complicit in uplifting white Nationalism.

The survey seems to indicate that people no longer have a taste for naming themselves as white Evangelicals, but that doesn’t mean the best of Evangelicalism has left Christianity. In fact, the way that David Bebbington describes Evangelicals really has nothing to do with how PRRI described it, nor how it is currently culturally defined by media people, or by people who call themselves Evangelicals. Here’s how Bebbington describes the four characteristics of Evangelicalism (from this post):

David Bebbington’s historical definition is based on the Evangelicalism that was alternative to the Anglican church in Britain in the 17th, 18th, and 19th century. His four characteristics (see here):

Biblicism: all essential truth is found in the Bible (this is more nuanced that the fundamentalist “inerrant” or even “infallible” notions).

Crucicentrism: a focus on the atoning on Jesus (again, this is not a focus on Penal Substitutionary Atonement, which is a hallmark for many Evangelicals with whom I fiercely disagree).

Conversionism: the basic idea that people need to be changed and transformed (into followers of Jesus).

Activism: the belief that the gospel needs to be expressed practically and earnestly.

If you had to pin me, I’d probably name myself as an Evangelical according to the above characteristics. But practically no one thinks of those four characteristics as “Evangelicalism.” What’s good about that is that those four characteristics, in my opinion, represent healthy Christianity, or at least part of it. And they very well may be transmitted to other parts of our faith (and already have been). So the worry about those characteristics going extinct from our faith as we lose white Evangelicalism is fraught. They are simply moving to other places in our faith. The death of white Evangelicalism does not mean the death of the best of the movement.

Are we reclaiming Christianity?

Today, white Evangelicalism is a sociopolitical movement that’s essentially impossible to separate from White Nationalism and the Republican Party. For the health of Christianity, it is essential that we marginalize those radical voices, as we focus on reclaiming Christianity, at large, not just Evangelicalism.

And honestly, it looks like we are reclaiming Christianity. White Christianity is on the rise, but more importantly, Christianity remains stable in communities of color. A quarter of Christians 2020 remain people of color. And most Black folks, Native folks, and Hispanic folks are also Christians as well:

Further, as it turns out, white Evangelicals have the oldest median age, with white Catholic, white mainliners, Black Protestants, and Hispanic Catholics and Protestants all younger. It looks very clearly like white Evangelicalism is dying. And its death makes way for new Christianity to form. As you saw above, the percentage of white nones are lowering, and Christians are increasing. Not everyone who currently identified as a non-Evangelical Christian was necessarily leaving White Evangelicalism; some may have been leaving their lack of affiliation altogether.

One more reason I am encouraged by PRRI’s survey is it showing us that Christians of color are a stable presence throughout Christianity and make up a larger segment of the Democratic Party than their white Evangelical counterparts make up of the GOP. Moreover, 26 percent of Christians between the ages of 19-28 are of color, whereas the same is true of all white Christians in that same age-range. As Christian leaders, that shows us where to focus our efforts: including young people of color in our churches, and no longer organizing around older, white people, who are dwindling in the share of their population. Focusing on keeping white Evangelicals happy in our congregations will always come at the expense of the young people of color, who are also more progressive.

We need intention, not merely incident

It seems like Christianity in the United States is changing, and it seems like it is rejecting false prophets and witnesses in our faith. That is a good thing for the health of the church. The prophetic witness of oppressed Christians in the U.S. has shed light onto this evil that has invaded our churches, and people are fleeing. We are fortunate that they are fleeing to other churches. But I must remind all of us that individual liberty to leave racist nationalist churches is OK, but it’s not the best way to move forward. This migration appears to be incidental, but we must be intentional about changing our churches. People falling away from the false witness of white Evangelicals are lucky to find other places for faith.

The writer of 1 John is battling a similar problem. They have people with dangerous theology in the communities he’s writing to. He writes this sentence, which I believe speaks to the current moment: “They went out from us, but they did not belong to us; for if they had belonged to us, they would have remained with us. But by going out they made it plain that none of them belongs to us.”

What we’re seeing is not the white Christian nationalists leaving Evangelicalism, but rather the authentic Christians in those churches leaving them and hopefully finding new faith. That’s not good enough for the future, but it is a step in the right direction. We still need a prophetic witness to speak out against Christian Nationalism and those whose brand of political pluralism keeps us from speaking out. We still need brave pastors and leaders who name evil in our faith and our congregations. We need to know that it is OK to expel the wicked person, to treat them as a Gentile or a tax collector. And the fissures and damage that white Christian Nationalists have brought to the church is worthy of using the keys Christ has granted us to loose and to bind. For many churches, it is clear, who the wheat is and who the tares are, who the sheep are, and who the goat are. Addressing those folks and either converting them or letting them go is essential to creating churches that are safe for discipleship and growth. I want to do my part in creating those safe places as well.